The year of collective action

It was a year people banded together to sound a clarion call for the rights of the individual. #MeToo, farmers' marches, religious reformswhat made 2018 the year of the collective?

A sea of women is gathered in protest, wielding placards, banners and babies. The toddlers have been given placards too, as many as their fingers can hold. There is a cascading effect to the demonstration, almost as if the multitude threatens to spill out of the frame.

The energy in the photograph is palpable, possibly fuelled by anger and hope. It’s from 1981—a protest against the rape and murder of two school-going girls, sisters Namita and Sunita Bhandari. In the kingdom of Nepal, these women’s marches had deep political ramifications as the murder suspects were members of the royal family, and investigations were headed nowhere. An echo from this was felt this year, when mass demonstrations and candle marches took over Nepal to demand justice for the rape and murder of 13-year-old Nirmala Panta in July. On Twitter, under the hashtag #JusticeForNirmala, people across Nepal started pressurizing the government to pin down the suspect.

Photographs from the 1981 women’s demonstration were part of a travelling exhibition this year, called The Public Life Of Women: A Feminist Memory Project, shown in Patan, Nepal, and Delhi. One of the curators, NayanTara Gurung Kakshapati says the exhibition had been in the works for a while, but gained strength from the #MeToo movement. The conversations on sexual harassment and gender-based violence definitely had something to do with the urgency of this exhibition, she says.

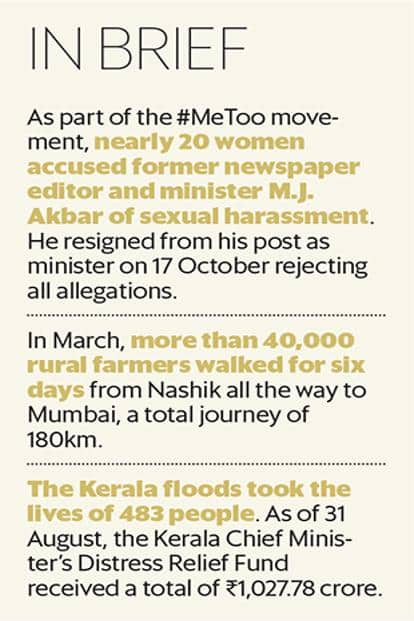

This is what the social media-driven #MeToo movement in India this year must have looked like on ground. Screenshots and social media posts became protest banners. Whether the women chose to reveal their identities or stay anonymous, their posts became formidable documents and evidence that forced men accused of sexual harassment, many of them in influential positions, to step down.

Like #MeToo, significant mass movements unfolded in India all through the year, evolving as part of a continuum. From the farmers’ marches to Delhi and Mumbai to those organizing relief for Kerala floods victims; from the Supreme Court verdict scrapping Section 377 to its verdict that upturned prohibitive gender traditions at Sabarimala—this was the year when people banded together to sound a clarion call for the rights of the individual.

But, protest rallies, hashtag movements and vigils are not new. What made 2018 different?

The year of the collective rests on a paradox, almost along the lines of Newton’s third law. Globally, we have been seeing the effects of divisive politics. Take Trump’s support for increased border wall funding and family separation policy, for instance. As if in response to his anti-migrant policy, a slow-moving caravan of 3,000 refugees is headed for the US, and is finding strength in numbers, much like a shoal of fish. The caravan originated in Honduras, fleeing extreme street violence and drug cartels. Time reported, “…the migrant caravan shouted to their companions squatting on the international bridge. ‘Venganse,’ they chanted, come on over."

Call for action

In India, caravans that emulate this spirit have emerged. This August marked the first anniversary of Karwan-e-Mohabbat, human rights’ activist Harsh Mander’s response of solidarity against hate politics and communalism. New ones that are slowly burrowing through deep patriarchal structures have been initiated too. Instagram account Scene and Herd posts on sexual harassment and abuse in the Indian art world. Leading contemporary artist Subodh Gupta was outed on one of the recent anonymous posts on the account, which currently has a following of 4,100. Gupta later denied the allegations.

In Kerala, new groups are addressing the Sabarimala row, allegations of rape against priests of the Catholic and orthodox churches, and sexism in the film industry. Save our Sisters (SOS) Action Council was formed in September, three months after a Catholic nun alleged that she was raped multiple times by Bishop Franco Mulakkal of the Jalandhar diocese from 2014-16. Despite the initial silence of the Catholic Church, the nun found that many were ready to lend a voice to her cause, right from sending a letter to the Vatican to filing a petition in the Kerala High Court. Among those who saw that the nun’s immediate concerns were symptomatic of a larger issue, was the Kerala Catholic Reformation Movement. The group championed her cause through hunger strikes and appeals, and went on to form SOS Action Council in order to make a lasting change in the Church. SOS has about 30 representatives from across Kerala, formed specifically to raise awareness about violence against women in the Catholic Church. Since its formation, SOS has been instrumental in getting Mulakkal arrested (he was later let out on bail).

Sandhya Raju, a Kochi-based lawyer volunteering with SOS Action Council, says the group’s members are not limited to human rights activists. There are environmentalists, trade unionists and feminist thinkers, too. “It was the first time that the nuns had come out to publicly protest the rape, and they had people supporting them. The whole world was looking at these protests," she adds.

SOS knows that these allegations are not isolated incidents—these are structural, running deep and gaining legitimacy through patriarchal practices. In the case of the Sabarimala row, where devotees protested the Supreme Court’s verdict in October to allow the entry of women of all ages into Kerala’s most famous pilgrimage centre, SOS exists in its parallel avatar—a collective called Arpo Arthavam (“glorifying the period" in Malayalam). The collective has been following the case of activist Rehana Fathima, who had attempted to enter the sanctum sanctorum of the Sabarimala temple in October, and was arrested through the intervention of the Kerala government after temple authorities complained.

The agrarian crisis has also led to new collectives, such as the online campaign Dillichalo.in, formed in November. The website was launched as a response to the farmers’ march to Delhi in November, in which they demanded that the centre address key issues such as credit crisis, farmer suicides, and rights of landless labourers.

Classes come together

Farmer movements in the country have been on the rise since the late 1970s . They have been spurred on by the increasing stakes against the rural sector as well as the need for agrarian mobilization by political parties. But the movement had largely been viewed as an event happening on the sidelines of the country, and mainly as an exercise by the Left. The divide between the urban elite and the rural and Adivasi famers was always there, but 2018 blurred the boundaries. Over the year, three farmers’ marches made national headlines—the Kisan Long March from Nashik to Mumbai in March, the Bhartiya Kisan Union in October, and the All India Kisan Sabha in November.

P. Sainath, award-winning journalist and founder of the People’s Rural Archive of India stated in an interview to a magazine that the Nashik-Mumbai march was inspiring because it was the first time in the last 36 years in Mumbai that he saw the middle classes show up in large numbers to support the farmers.

There were theatre actors and musicians who walked with the farmers as they entered the city; residents from a Mumbai suburb who showered them with flowers; lawyers who offered to file PILs on their behalf. Dillichalo offered a direct line of support to the November march, and, in the website’s own words, it is “not the culmination but the beginning" and “a response to the need for new radical forms of urban and rural solidarity".

The social network

The agrarian crisis rippled into our living rooms, right from the moment a video of the farmers holding red flags and streaming down Kasara Ghat en route to Mumbai was circulated on social media. That video, shot by Dr Ajit Navale, secretary of the Akhil Bharatiya Kisan Sabha, was the turning point; it laid bare a collective stride for a common cause.

The impact of social media was also seen in the environmental disaster that was the Kerala floods. Relief and rescue efforts poured into the state, largely because social media made viewers feel that something had gone horribly wrong right in our neighbourhood rather than in one of India’s faraway, southern states.

A networking app called QKopy, for instance, helped host the Kozhikode traffic police on its platform, so that users could get accurate information and curb the spread of fake news during the floods. The app was originally launched in May to achieve a similar end during the Nipah virus outbreak. Rajiv Surendran, one of the co-founders of QKopy, says that it’s important that tech start-ups help build a responsible social culture. It’s a warning against social media frenzy, such as the nation-wide lynching trend this year that got fanned by WhatsApp rumours.

While #MeToo raised concerns about how its second wave wasn’t inclusive enough or intersectional enough, social media continued to play a pivotal role. The movement picked up pace in its second wave this year, after the hashtag was first used in 2017 by the bahujan law student Raya Sarkar who kick-started the Indian arm by publishing a list of alleged sexual predators in academia (Sarkar later deleted the list). But, it was this year that many realized the movement needed more than firsthand accounts. They needed a support system as well. Professionals came forward to offer their services, for free, to survivors who sought legal help or trauma counselling.

Scherezade Sanchita Siobhan, a Mumbai-based clinical psychologist and therapist and practising psychologist was among those who volunteered. Her number was added to a crowdsourced list of free services available to survivors. Siobhan says she was already aware of some of the stories before they were posted on social media. “What made me want to jump in was that I had clients who had the courage to go public with their stories. That was the tipping point—that they would speak about it publicly. This was bound to occur, for the simple reason that with social media people had access to a non-hierarchical way of expression," she adds.

Siobhan also observes that as a woman, you are expected to be binary—you either agree or you don’t, and if it’s the latter, then you are labelled an anti-feminist. “There were many who didn’t pick a side, especially older women. #MeToo should continue being democratic, without centres of power, but there must be on-ground work, too," she says.

Whether it was #MeToo or the Kerala floods, this was the year we saw the power of the collective play out in full public view and in real time.

In Nepal, women activists held a peaceful semi-nude anti-rape demonstration in August. They gathered at Maitighar Mandala in Kathmandu, one of the several public grounds where the Nepalese government had banned protests. All the women were arrested. In light of this, Gurung Kakshapati points out that in the last century, not all women’s movements were “successes". “But, that’s not the point," says Gurung Kakshapati. The point, as she phrases it, is to remember them, and to celebrate them

-

FIRST PUBLISHED29.12.2018 | 01:20 PM IST

-

TOPICS

- For all the latest Fashion News, Lifestyle News, Food News, Smart Living, Health Tips, and Relationships, only on Mint Lounge.