Critics are fond of pointing out that good novels understand the passage of time and therefore know how to manipulate the reader’s perception of it. Allow me to offer a corollary: Good graphic novels understand space and all things spatial. In Art Spiegelman’s Prisoner On The Hell Planet, a mini-comic within his graphic memoir Maus, the increasingly claustrophobic visuals of a prison cell block are used to convey the protagonist’s struggles with mental health. Richard McGuire’s Here (2014), one of the oddest and most daring graphic novels of the 21st century, follows the same physical space across centuries—a forest, an arid wasteland, various kinds of human settlements. A forest fire in medieval times is placed alongside a 21st century resident coughing, creating a sense of cause and effect that’s both absurdist and not. Space matters in the world of comics because of bold gambits like these, exploiting the medium’s unique power.

Anoushka Khan’s debut graphic novel, Still Life, understands physical spaces. Khan understands how good storytellers tether certain emotions or ways of thinking to specific places, and the text is marked by impeccable atmospherics and a creeping sense of melancholia. There isn’t a whole lot of plot—Pinky the protagonist travels uphill in search of her missing husband, Pasha, whom she has known since childhood—but that is rather the point. Still Life’s great subject is the agony and necessity of silent contemplation and Khan’s black and white artwork establishes this tonality quietly, efficiently.

The brooding often happens outdoors, and not only because Pinky is searching for Pasha at an old cottage-on-top-of-a-hill belonging to his family. In pre-modern texts stretching all the way back to Homer’s epic poem Odyssey, existential themes were frequently encoded within “nature scenes”. Soldiers would see their lovers’ faces in constellations, nature deities would intervene on behalf of pious mothers, kings and queens would receive “signs” guiding them to their next course of action.

“Can you see the shapes in the hills?

Yes.

Which ones?

Over there, the crooked nose and the big chin.

The great big head. Can you see the five toes and the bunion?

Where? That is not a bunion, Pinky.

It looks just like my grandmother’s foot.”

Consider this conversation between Pinky and Pasha, during a flashback sequence at the beginning of the book. A part of the newly anthropomorphised hill resembles, it is said, the bunion on Pinky’s grandmother’s foot. Soon after, Pasha promises Pinky he will “take her there, one day”. Both statements echo Pinky’s current predicament: trundling up and down the hills, with nothing to show for her efforts. Since we know how their story is going to play out, this seemingly innocuous exchange works as foreshadowing.

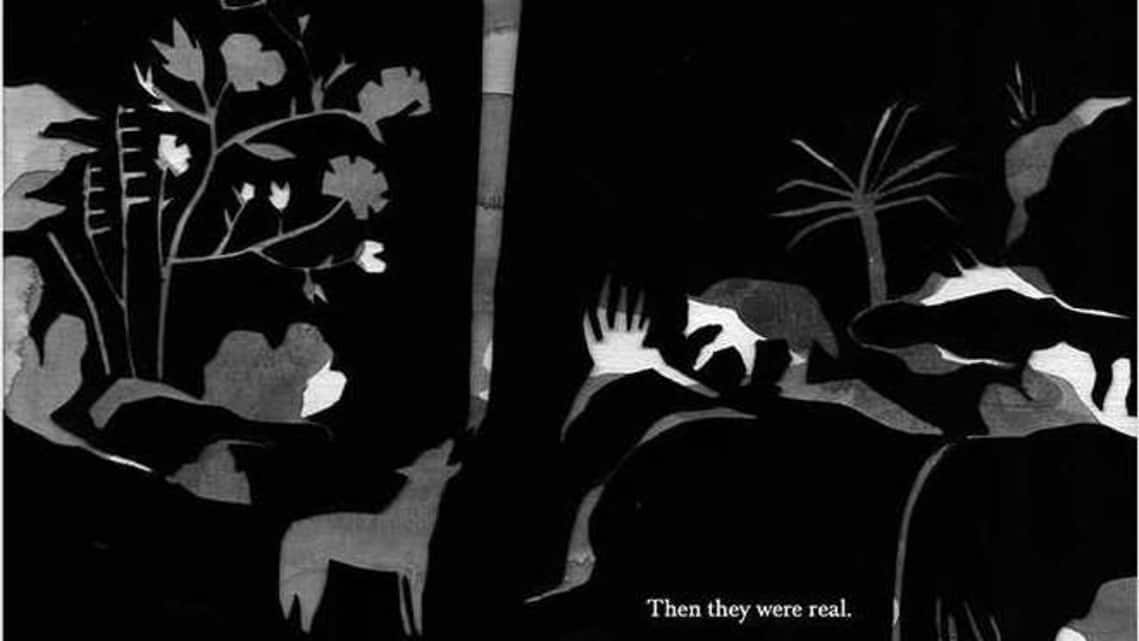

Animals are a crucial part of the existential puzzle here too. In their mutilations, deprivations and hungers, Pinky tries to make sense of her past and present. A lizard with a missing toe on a wall leads to a stunning, mixed media sequence (watercolours, acrylic and pencils do the heavy lifting in this book, collages pop up every now and then) where she imagines a hundred thousand replicas of the lizard covering the wall entirely. Pasha’s mother feeds Pinky and tells her a story about a jackal struggling to feed her hungry children.

What exactly is going on here? The academic discipline “animality studies” offers some answers. From Aristotle (his treatise De Anima or On The Soul) to Jacques Derrida (the essay The Animal That Therefore I Am) to contemporary luminaries like Mel Y. Chen (their 2012 book Animacies: Biopolitics, Racial Mattering, And Queer Affect)—this area of study suggests an important epistemological role for animals in the human psyche. It also investigates the duality offered by all animals—namely, that they are similar to humans in certain contexts while being among the first “not-me” beings encountered by the developing human mind.

This duality is highlighted beautifully by the contrasting attitudes of Pinky’s parents. Her mother is a biologist who tries to reinforce the idea that animals are just like us (“see, just flesh and bone,” she comforts Pinky when the latter sees a carcass in childhood). Her father, on the other hand, represents the “not-me” aspect, the inscrutability of nature. An archaeologist, he tells her several skeletons, both human and animal, were found in the Indus Valley ruins. Their cause of death could not be determined—mirroring the abruptness and cruelty of Pasha’s disappearance.

These two points of view are separated by a wordless page with a chessboard-like grid (Pasha and Pinky played chess as children) with various animal fossils (or impressions of these) embedded in individual squares. Still Life rewards close reading, which, I would argue, is especially important for graphic novels.

Khan’s art alone would have been worth the price of this book, to be honest. The fossil-grid and the mutilated lizard mosaic are just a couple of the impressive artworks that drive her narrative. The watercolours that make up most of her landscapes are just as good. Most importantly, the art conveys the emotional texture of her story quite effectively; the mystery, the pathos and the fabulism. At no point does it seem like a page could use more or less words than it does, a tricky balance to achieve, particularly in a debut work.

Comics and graphic novels, especially of the superhero kind, are often associated with “noise” on the page; the clamour of action, the ceaseless hum of activity. But there is, and always has been, a parallel tradition of sequential art preoccupied with silence. From pre-World War II masters like Lynd Ward and Frans Masereel to modern-day creators like Shaun Tan, comics artists have created some unforgettable, wordless graphic novels. Closer home, George Mathen aka Appupen’s “Halahala” books (Moonward, Aspyrus et al) are great examples of this subgenre. Still Life, while not being entirely wordless of course, channels some of the meditative silence of these works. This is an accomplished, ambitious debut well worth reading and re-reading.

Aditya Mani Jha is a Delhi-based writer.